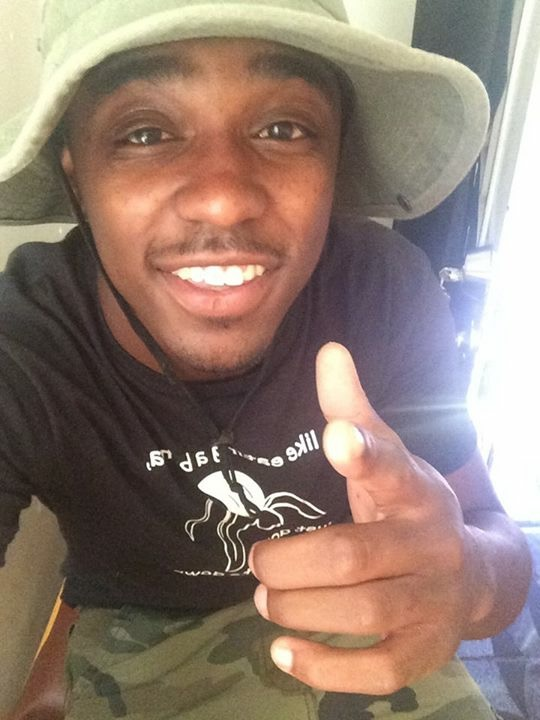

On June 6th, 2016, in Columbus, Ohio, 23-year-old Henry Green, and a friend, Christian Rutledge, were walking toward the house where Green lived with his aunt, when a white SUV with blackened windows abruptly swerved in their direction.

From the car, two white men in casual clothes, one in camouflage cargo shorts and the other dressed in all black, jumped out with guns drawn. Before he could identify Columbus Division of Police officers Jason Bare and Zachary Rosen as law enforcement, 24-year-old Rutledge claims he heard one ask, “You gonna pull a gun on me, motherfucker?” He saw no badges. Shots rang out.

Henry, struck seven times, fell to the ground. His neighbor, Jamar Jordan, saw his friend fight for life on the sidewalk and told him to focus, to try and stay present. Others started to crowd. In a video taken by a bystander just after the shooting, police move about quickly and Jamar can be seen pacing yards behind Henry, who is on the ground in handcuffs, being given CPR while his blood pools.

Rutledge was arrested and held for five hours without knowing the fate of his friend—known to friends and family simply as Bub. Bub’s family rushed to the hospital, where he was taken and pronounced dead just over an hour after the officers shot him. Additional police were called to the site of the shooting, then more were sent to the hospital because relatives there “were upset,” according to police spokesperson Rich Weiner. Bub’s parents were never allowed to see his body.

The Columbus Division of Police (CPD) issued its version of events in the hours after his death: Bare and Rosen said they’d spotted Bub “brandishing” a gun and ordered him to drop his weapon. They claimed that he began shooting at them, so they returned fatal fire.

“They hopped out so fast I thought they shot through the window,” Rutledge would later tell the Columbus Dispatch. The officers were operating as part of the Community Safety Initiative, a program designed by the CPD and supported by the city, aimed to target neighborhoods deemed “vulnerable” during summer months through increased police oversight. But those officers were operating as surveillance and technically advised to call a cruiser in the case of an incident.

Bub’s mother, Adrienne Hood, questions the officers’ explanation. The situation they described was out of character for Bub and Ohio is an open-carry state. So even if he had a gun, she posed, “Where was he breaking the law?”

From 2013 to 2017, members from the department fatally shot 28 people, according to Mapping Police Violence. Twenty-one of them were black like Bub.

Every time a Columbus police officer kills a citizen, two sides to the story exist. But aggressive behavior by officers often goes unchecked by the department—which is backed by a powerful police union—and decades of non-indictments from the prosecutor’s office for those who kill shows how, in Ohio’s capitol, the victim’s families are often silenced and officers’ perspective becomes the main narrative.

The CPD has operated this way for decades—a narrative not dissimilar to other police departments across the country. But how does that sort of aggression, that deep-seated racism, become institutionalized into an organization? A closer examination of CPD history details a pattern and practice of brutal racist behavior that has gone long unrectified by department superiors, cowardly city leadership, and the Department of Justice (DOJ).

Bare and Rosen had volunteered to patrol as part of the Community Safety Initiative, which was designed in 2002 to increase “staffing/proactive enforcement” in zones throughout Columbus. The policing strategy changed names repeatedly—the Summer Strike Force Initiative, Summer Anti-Violence Initiative, Summer Anti-Gang Initiative—but has operated continuously as an overtime operation.

“At its core, CSI is a funding mechanism for the division to deploy more officers during the summer months,” Commander Gary Cameron said in an intra-division “after action” report in September of 2016. Of the $750,000 program budget for 2016, 98 percent was sworn overtime.

(Photo: Courtesy of Walton + Brown, LLP)

Police credit the CSI program for the city’s steady crime decline, but residents say black neighborhoods are profiled and over-policed without the addition of extra surveillance, and call cops like Bare and Rosen “jumpout boys.” The majority of contact occurs between citizens and police stationed in Zone 4, the majority-black Linden neighborhood where Bub died. Other zones had two officers each, Zone 4 had 10. It’s where Adrienne Hood grew up; her sister still lives there.

In the “after action” report, city safety director Mitch Brown says the program “prevents violence.” Bub, whose death is called the “most significant plain-clothed event” of the summer, is mentioned only three times.

“Despite the outcry over the Henry Green shooting incident, [CSI] remains as a viable and effective program for the division,” the report reads. “While the statistics do not play out in dramatic fashion after the 12 year [sic] one fact is clearly evident, Columbus is safer and there are relatively fewer violent crimes perpetrated upon our children.”

After Bub’s death, the chief of police said publicly that the role of CSI officers was to surveil. The report concludes with the recommendation to make that policy official: Cameron suggested the program would formally become a surveillance team, requiring plainclothes officers to work in direct proximity to CSI uniformed officers. He also asked for two more officers per zone.

Bub’s family immediately called for the end of the initiative. In February of 2017, Ginther instead announced that Columbus would extend the program year-round. Nine months later, after meetings to discuss the fractured relationship between police and some Columbus citizens, the mayor announced a plan to nix CSI in exchange for $2 million to help ensure overtime costs for “neighborhood safety strategies fund,” which would pay for strategies like a year-old Linden bike patrol used to “gather information that would help hold those responsible for violent crimes accountable,” and a new foot patrol, whose pilot period would be tested only in the Linden area.

The day after Green’s death, the CPD notified his family to address the next steps. Bare and Rosen’s actions would be reviewed internally by homicide detectives, then passed along to a police disciplinary review board and the Franklin County prosecutor’s office. The prosecutor, Ron O’Brien, would decide if a criminal indictment should be filed against the officers.

In O’Brien’s 20 years in office, no officer has been indicted for an on-duty fatal shooting. Bub’s death came during an election year, and the relationship between his office and the police department was often discussed. Green’s family worried his case would move along as so many other police shooting deaths in Franklin County: The department would justify the officer’s actions, arguing that the shooting was within policy because they feared for their lives, then a grand jury—a court proceeding held in private that, around the country, typically favors police—would fail to indict.

In a telling statement from 2015 about his attitude toward such trials, O’Brien said that, “nine times out of 10, we’re [the prosecutor’s office] presenting a case that otherwise wouldn’t be presented because we don’t think a crime was committed. There are probably only a handful of these cases over the years where it was even close.”

Simply put, he believes officers act within their legal rights when they kill on the job.

The family asked for the DOJ to investigate the shooting, and requested a special prosecutor to oversee the indictment process. This demand was not met, despite letters to their mayor, Ginther, and prosecutor O’Brien.

Four months after Green was killed, Commander Gary Cameron told reporters that CSI officers are “kind of handpicked.” “They’re our superstars,” he said.

Bare previously worked at a juvenile detention center, where he received a written reprimand for leaving a suicidal juvenile alone. He applied to work for two departments in other counties before he became an officer with the CPD.

Files from his interview reviewed by Pacific Standard reveal a drunk driving habit: During the polygraph, Bare admitted to driving while intoxicated on eight occasions in the prior year, and told interviewers that he’d driven after drinking four beers just two weeks prior. (Columbus minimum expectations for hire demand a conviction for drunk driving, not just admittance.) He was still hired.

During a semi-annual review in 2011, a committee of commanders working in the Employee Action Review System found issue with Bare’s tactics and force—he once tased a “suspect” who turned out to be a runaway child who was not criminally charged. A memo about his pattern of force was sent to a sergeant who disputed the findings and recommendations, instead of correcting the issues. Bare called a citizen “dumbass” and was given documented constructive counseling—the initial step of formal corrective action, “but not an action of record“—in 2013, the same year he began patrolling as part of CSI.

(Photo: Alli Maloney)

In March of 2014, Bare and another officer responded to a medical call and ended up brawling with a neighbor, whose door they attempted to kick down after the man allegedly held up his middle finger. Several witnesses said Bare tackled the man, who told investigators Bare called him a “dread head,” and “dope dealer,” among other names. All allegations were sustained and exonerated by his superiors.

Reports of Rosen’s own aggressive behavior had also been called into question prior to Green’s death. In 2015, Rosen stopped his cruiser in the parking lot of a hardware store while on patrol and approached a hot dog stand with his partner. Dustin Fistick emerged from the store and took a picture of the patrol car, which he believed to be parked in a fire lane, and made a comment to the officers.

Fistick got in his car and drove away. Within six minutes, he was pulled over and given a citation for failure to signal. He filed a complaint with CPD internal affairs.

Rosen told investigators that he “consciously and purposely” decided to follow Fistick until he found a legal reason to stop him, a practice he admitted to having done before. “I want(ed) to know who this guy is,” Rosen said. “Maybe he hates police … with what’s going on around the country with people attacking police, ambushing police officers, I don’t know what this guy’s mindset is.” Chain-of-command said Rosen “did not exhibit proper conduct and self-control” and recommended non-documented verbal counseling.

Yet those measures were half-steps at best, says Anthony Wilson, who joined the CPD in 1991 to make “changes that needed to be made.” He first started as a patrol officer and stayed with the department for over two decades.

Wilson spent three years in internal affairs. He considers the finding in Rosen’s case consistent with the department’s internal lack of substantial accountability, which is why he left in 2013. Wilson, who now works as assistant chief in a neighboring city, described his former employer’s hiring system as flawed and out of date. He served as supervisor to the CPD’s recruiting unit from 2007 to 2013 and found blatant improprieties and deliberate manipulation of the background selection process.

“Non-documented counseling is basically me talking to you and saying, ‘don’t do that again,'” Wilson says. Yet harsher discipline by form of documented counseling can be flawed too. According to the department’s union contract, citizen complaints must be proven by the CPD to factor into discipline. They rarely do. If founded, a complaint only stays in an officer’s file for six months. Sometimes they don’t even hit the file because investigations take too long, Wilson explained. If an officer is disciplined, they can even use paid vacation days as substitute in lieu of suspension.

THE END OF SOLITARY CONFINEMENT: What is California going to do with “the worst of the worst”?

If the investigation against Rosen hadn’t resulted in a rare sustained allegation—even though he received no additional training to rectify—the record would not exist one year later, when he shot Henry in South Linden. Columbus police files are routinely destroyed every four years, which further limits accountability.

When asked why an officer with a history of aggressive policing like Rosen might be put in plainclothes or unmarked vehicles, operating as surveillance as part of the CSI, Wilson cited internal and public desire for proactive policing and the applause for “go-getter” cops.

“The definition of a ‘good officer’ to the masses is one that is aggressive,” he says.

Officer Bryan Mason is another of Wilson’s “good officers” who also exhibited questionable aggression. Before he shot and killed 13-year-old Tyre King in September of 2016 for allegedly holding a toy gun, the nine-year veteran of the force had been investigated at least 60 times for issues such as excessive force and inappropriate language, 25 of which required medical attention. Not one issue was sustained by internal affairs. He’d killed before too: In 2012, he shot and killed a man who refused to discard his gun. Supervisors cleared him of wrongdoing. A year later, Mason shot a man who ran away from a traffic stop and was found within policy when he told a police review board that he feared for his life. The black 22-year-old, who survived, claimed to have never pulled a gun on the officer.

Tyre King was five-feet-tall and weighed less than 100 pounds, but Mason said he fit the description of a 19-year-old robbery suspect and shot him three times in September of 2016, most likely while he was running away. Like Bub’s, the CPD framed King’s death with immediacy. Pappas, the FOP president, told the Columbus Dispatch that Mason was a “really, really good officer.” Ginther called Columbus the “safest big city in America.” The CPD’s chief, Kim Jacobs, defended her officer’s actions from the steps of city hall, holding up a full-page image of the toy gun King reportedly carried.

Mason received psychological counseling and was given desk duty. Bare and Rosen returned to patrol within weeks of killing Bub.

Rosen was eventually reassigned to non-patrol duty in 2017, after he was shown striking Demarko Anderson in the head in a video that was recorded by a bystander and uploaded online. He was found to have used unreasonable force, and the investigation awaits just cause review.

In the video, Anderson, who is black, is shown restrained by another officer, and can be heard yelling: “I got cuffs on, sir! Are you serious?” at Rosen, who appears from out of frame to stomp on his head. Rosen, who used profanity throughout the incident, told investigators he thought the 22-year-old still might be armed though, as reviewers found, Anderson wasn’t searched for several minutes after the strike.

In a 2012 memo reviewed by Pacific Standard, Wilson told Jacobs that, instead of judging policing recruits based on the raw score earned on their Civil Service Exam, he found that the background team “hand-picked” candidates who “look like they will make it through the process.”

Applicant background files for top-scoring candidates were lost, misplaced, or forgotten. As a result, some were never contacted by the background unit, though they earned higher scores than others who were hired. Confidential medical and psychological documents pertaining to past candidates, “current and future officers,” were found in an open desk drawer—information that could have prevented some candidates from being employed by the city. And there was nepotism: An academy cadet was directly told his application would be processed after relatives of current CPD employees.

The number of black officers in Columbus has always been significantly out of proportion to the number of black citizens in the city. One month after Bub was killed, the 125th recruiting class was inducted into the CPD. Of the 27 new officers, only two were black. Since then, another majority-white recruiting class of 33 officers has been inducted.

Wilson was responsible for minority recruiting and also served as head of a diversity recruiting council. Under his watch, more women and minorities were deemed eligible to hire, but recruiting held no bearing over the actual hiring process due to the CPD’s “fragmented selection process,” he says. Some portions of recruiting, background, and training units fall under entirely different chains of command—for example, hiring is handled by the city’s civil service commission—which makes communication about the process often incoherent.

“I was accused of trying to ‘dumb down the process’, and we know what that’s coding for,” Wilson says, alluding to stereotypes on black intelligence. He doesn’t believe every cop in the department is racist, but that the CPD has operated as a broken system.

Ginther says the city is listening. In November of 2017, the government and department announced that community evaluators would be added to the committees responsible for hiring to help ensure that the city’s police and fire departments “reflect the great diversity” of Columbus, enlisting Public Safety Director Ned Pettus to develop a plan to double the number of minority officers in both departments within the next 10 years.

Columbus is the 14th-largest city in the United States. The CPD employs over 1,800 law enforcement officers, the overwhelming majority of whom are white. Black people make up less than a third of citizens in the CPD’s total jurisdiction, but Columbus police kill black people with the greatest frequency of any race.

It is not easy to measure how police shootings in Columbus compares with other cities around the country. Over 17,000 law enforcement agencies exist in the U.S., and, like the others, the CPD is not required to report data on police shootings to the DOJ. Neither standardized recruitment processes or national standards exist. Journalists have provided the best records on police killings so far.

CPD history does not lack violence against black boys and men like Bub. Newspaper records show that black Columbus residents have reported mistreatment by police with great frequency for decades. In 1971, a white officer was acquitted after he shot a black 18-year-old 13 times with an M1 carbine modified into a machine gun. Four years later, that same officer, Robert “Machine Gun” Morgan, was fired, then rehired, after brutally beating three black restaurant patrons. At the same time, black and female officers were suing to be hired by the CPD. Forced hiring quotas were implemented in 1975, requiring that 14.9 percent of each new trainee class be black.

In 1979, 16-year-old Keith Burke was running away from white cops in plainclothes when they shot and killed him. Columbus native Elias Kunjenga, 63, is a minister and activist who worked with Keith Burke’s father. They raised their children together on Hallidon Avenue, where both families lived. The “killer racist mentality” within Columbus policing follows from one generation to the next, he says. “We’ve been trying for a civilian review board for 40 years.” (In 2016, a local NBC outlet reported that FOP president Pappas said the organization “adamantly oppose[s]” such a review board, which citizens are still working toward, citing the use of a grand jury as one of the many ways citizen complaints against police are reviewed.)

Kunjenga’s brother, Calvin Reynolds, was 20 years old in 1982. Two off-duty officers shot Reynolds six times for allegedly using a screwdriver to break into a car to steal an 8-track cassette tape. They were cleared by a grand jury, and the Reynolds family was eventually awarded a small settlement. “But that doesn’t replace your son,” Kunjenga says. “It doesn’t replace my brother.”

Ollie Stubblefield, who founded a minority police and fire organization called Police Officers for Equal Rights, spoke out in Burke’s defense, and was pushed out from the police force. Officers who spoke out about his firing—like Charles Grooms, who wrote an op-ed to the Columbus Dispatch about Stubblefield’s character and volunteered as protection for the marked officer and his family—received threats. (Grooms left the force in the early 1980s, and told Pacific Standard that he believes he was edged out for showing support to Stubblefield and other black officers who spoke out against mistreatment.)

In court, black officers challenged the tight-knit culture they faced in the department, which was rife with daily microaggressions and directly racist behavior. In 1985, a court found the department discriminated against black officers in promotions, assignments, and transfers. Still, five years later, a federal judge ruled that the department could keep using a promotional test that had an adverse impact on black candidates.

As of September of 2017, the CPD was facing at least two dozen lawsuits, including one filed on behalf of former CPD officer Kevin C. Morgan II in 2015 alleging that black employees have been “driven out” of the department in a “pattern of race discrimination and retaliation.”

Wilson points to Stubblefield and James Moss, another outspoken leader of the Police Officers for Equal Rights, as an example of the CPD’s “retaliatory” mindset for those who break the “thin blue line,” by speaking out against police and in defense of the community.

Moss served as president of Police Officers for Equal Rights from 1990 to the present. In 1993, he sued the CPD for police records to document what he perceived as retaliation for his outspokenness against the department. When he was refused, Moss took the case to the Ohio Supreme Court and won. The CPD was forced to offer up thousands of documents for his review, throughout which Moss noticed a pattern of police abuse.

For the next two years, he took to the street to interview residents of Columbus, collecting and reviewing complaints from citizens to take to the DOJ. He left the force and became a substitute teacher. He hired help to record the statements on video and audio, which he hand-delivered to the DOJ in Washington, D.C., in 1995. They turned him away, requesting more proof, so he streamlined a form for citizens to sign if they felt their constitutional rights had been violated by the CPD. Every week, he gathered and returned these personal stories to Washington, connecting them to police policies and constitutional standards.

The DOJ eventually considered each of these statements—the first 10 of which were filed by black residents—as individual complaints. In 1996, because of Moss’ tenacity, the department agreed to formally investigate the the CPD.

Among CPD personnel, the DOJ found a “pattern or practice” of civil rights violations, including racial profiling, using excessive force, and making false arrests, especially against blacks, young women, and poor white people. Supervisors didn’t discipline officers, so abuses were condoned and continued.

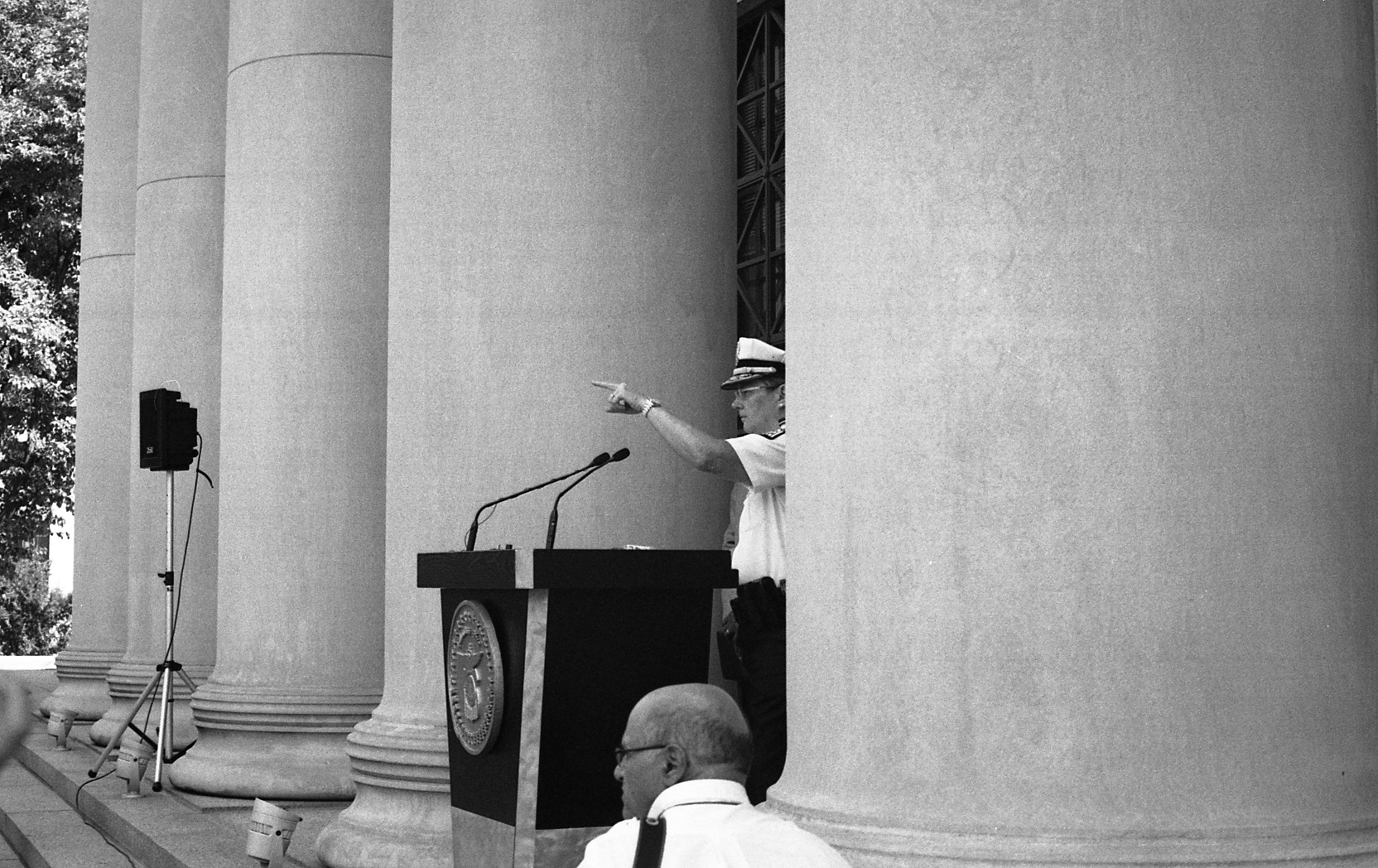

(Photo: Alli Maloney)

The government called for a consent decree, a type of agreement in which the CPD would commit to changing its culture under federal supervision without admitting guilt. (The practice of consent decrees between police departments and the DOJ started in Pittsburgh in 1997, and continues with more recent incidents like the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson.)

The CPD resisted the opportunity to change its legacy. Instead, the FOP took over the case and raised union dues to fight the charges. Though only the first such case ever brought on by the DOJ, it marked the first time a police department fought a civil rights case—and the first time that the DOJ has asked for a pending consent decree to be dropped.

Moss blames a Bush-era appointee John Ashcroft—”a Republican, pro-police”—as a major reason why the CPD successfully avoided a consent decree with a polite slap on the wrist, adhering to some, not all, of the DOJ’s suggestions, including the decision to install cameras in patrol cars. (The DOJ cited “strategic reasons” for dropping the suit.)

“The fact of the matter was, there was not a pattern of biased-based profiling or anything like that,” the CPD’s Sergeant Weiner recently told Frontline. “We felt like the government was coming in here and simply trying to bully us. We were doing the job right.”

Instances of police violence continued after the DOJ dropped charges against the department in 1999. Trae Darson and William King Jr. were both killed in 2006. Edward Claibourne Hayes Sr., 31, was shot and killed in 2008 while running away from a Summer Safety Initiative officer who approached him, days after another 16-year-old was shot and survived. In 2010, the CPD approached 16-year-old Da’Von Burt for looking “kind of suspicious.” He was shot five times and lived. In August of 2011, officers shot and killed two black 21-year-old men within three days: Obbie L. Shepard, who they accused of stealing a bike, and Francis Owens, who was attempting to resolve a fight with neighbors (“It was very odd, the number of attacks that officers were encountering on the streets,” Weiner said). Eight months before Henry was killed, officers killed 25-year-old Deaunte Bell in the parking lot of an apartment complex. The CPD framed the shooting as a “suspicious” traffic stop, but the car where Bell sat with friends was legally parked. He was shot six times in the backseat, including a fatal wound to the head. Two officers fatally shot Kawme Patrick, 25, less than one month after Henry’s death. In September, 13-year-old Tyre King was killed.

In each of the above listed cases, the CPD claimed that the victim carried, showed, pointed, reached for, or fired a weapon. Eyewitnesses contest the narrative put forth by the officers almost every time. The officers’ actions were deemed justified by the prosecutor’s office and backed by the department, mayor, and Fraternal Order of Police. Like Green’s, many families reported having been given little or no information about the circumstances of the death of their loved ones.

On March 13th, 2017, the CPD announced that it had “inadvertently” deleted 100,000 files of police cruiser video, further raising questions about accountability from activists in Columbus.

One week later, around the time Green would have turned 24, a grand jury determined whether or not a crime was committed by Bare and Rosen. Behind closed doors, the hearings lasted four days. Twenty witnesses were called in to testify, including Jones, Rutledge, and Adrienne Hood, who answered questions for 45 minutes. Bare and Rosen were the last people put before the nine jurors and five alternates on Friday, March 24th. Sean Walton, the family’s attorney, said that, when they arrived at the Franklin County Common Pleas Court, they were surrounded by other officers, walking in step.

O’Brien released a statement announcing the police detectives’ findings: According to the CPD, Bub fired six shots, Bare fired seven, and Rosen fired 15. The police detectives found “conflicting statements from multiple witnesses,” he wrote, adding the juror’s vote depends on “how credible” they find witness testimony to be. It came down to who they believed. By law, this testimony is closed to the public.

Outside the Common Pleas court, Green’s family and the community gathered in mourning. Police were stationed on horses across from the protesters, others waited at the corner, and state troopers stood just inside. A car swerved up to the curb and a white man rolled down his window to yell: “Innocent lives matter! Innocent lives matter!” while Tania Hudson, the mother of Deaunte Bell, described the college classes her son was attending before a police officer shot him in the head. (Neither officer was indicted.)

“He’s not wrong,” she said, once the crowd calmed. “Innocent lives do matter.”

The grand jury process may change moving forward, offering greater transparency for non-indictments in Ohio. In July of 2016, following several high-profile police killings in Cleveland and Cincinnati, a task force created by the Ohio Supreme Court recommend that the public be allowed to petition for release of grand jury proceedings in the case of a non-indictment.

When announcing the task force in February of 2016, Ohio Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor reminded her court that the justice system “belongs to the people.”

“‘We cannot make improvements if we are unable to see the need, consider the opportunities, or remain attached to the notion ‘but we’ve always done it this way,'” she said. Changes have yet to come.

Adrienne Hood was not surprised by the non-indictment. On June 1st, 2017, she filed a lawsuit against the city of Columbus that called the actions against her son “unconstitutional” and “racially motivated.” She hopes a public trial will bring Bare and Rosen out of the dark and into the public, where Bub has been since the moment he died. As of January, both sides in the case were giving depositions, which Adrienne thinks could take months to get through. “I guess after the depos, we go to trial,” she says.

“I can’t miss the opportunity to fight for my son,” she says. “If I sit and sulk too long … I will run out of time. I grieve, I yearn, but when I start going down and feel like I’m getting ready to have one of them crying things that I can’t shake.”

She pointed at Bub’s picture on a shelf in her bedroom. “I’ll be like: ‘Right, son. I got to get in this. I got to get this together.’ That’s what I do now.”